What is the Difference Between Organic Honey and Regular Honey?

Many of us choose to pay a little more for certified organic foods when shopping for groceries. For some, this is a choice for personal health: organic foods are less likely to contain harmful contaminants. For others the choice may be to support more natural, sustainable agricultural methods. For many both aspects come into play. While organic certification of food products seems like it should be straightforward, it gets complicated when talking about honey.

Sustainably produced honey fresh from our family farm to you

We’re confident that our honey is at least as free from antibiotics, pesticides, hormones, heavy metals and sugar syrups as any organic honey out there. Money back guarantee to anybody who proves otherwise. You can get 10% off your next order (up to $110 order value) when you buy our Canadian raw honey online here with coupon code CleanHoney.

Canadian Standards – Canadian Organic Regime (COR)

In Canada, organic certification of foods follows the Canada Organic Regime (COR) of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), implementing the standards and regulations developed by the organic industry in association with the Canadian General Standards Board, part of the Government of Canada. The CFIA goes on to explain that organic certification is performed by “Certifying Bodies”: “The CFIA enters into agreements with Conformity verification bodies (CVBs) provided these bodies meet the criteria established by the SFCR and CFIA. For the purpose of the SFCR, the CVBs are designated by the CFIA to assess, recommend for accreditation and subsequently monitor certification bodies (CB) meeting the applicable accreditation criteria as set out in the SFCR…The accredited CBs are responsible for the organic certification of food commodities”.

What this means for beekeeping is that “…the treatment and management of bee colonies shall be informed by the principles of organic production.”. This outlines what I would expect from organic food: that the inputs (feed, fertilizer, veterinary treatments, etc) be derived from organic sources and that organic agriculture respect the ecology, present and future health of the planet (including soil, plants, animals and humans as indivisible components of the planet), and even specifically includes the principles of fairness and equality of opportunity. What’s not to like about this?

For honey this means that beekeepers must use organic honeybee stock (continuous organic management for at least on year prior to receiving certification, or being moved into an organic apiary), organic wax, approved beehive materials, approved non-pharmaceutical veterinary treatments, and organic feed and supplements. Treatment with antibiotics and synthetic miticides1 (treatments to control the varroa mite parasite that has been decimating colonies in North America) are not allowed. Organic Certification is gained by application to one of the Certifying Bodies, and then passing inspections and audits. The records for each apiary (where the bees reside, commonly referred to as a “bee yard”), the apiary itself and its surroundings are inspected annually.

USA Standards – United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)

The USDA published the Formal Recommendation by the National Organic Standards Board (NSOB) to the National Organic Program (NOP) regarding apiculture (beekeeping) on October 28, 2010. Similar to the COR certification, the recommendation describes organic bee management principles including banned chemicals, organic feed and hive construction regulations, record keeping requirements, land management, and permitted forage sources. However, the USDA does not go so far as to actually certify American domestic honey as organic. Both USDA and COR do recognize organically certified honey from other countries, inspecting and certifying importers and packagers of organic honey from countries like Brazil, Mexico and India. The ironic result is that retail honey that has a legitimate “USDA Organic” logo on it cannot be American honey: It is imported honey that was certified organic in the country of production. I have read that some small honey producers in the United States do label their honey as “USDA Organic” and, unless somebody complains, will generally get away with it.

Things get complicated

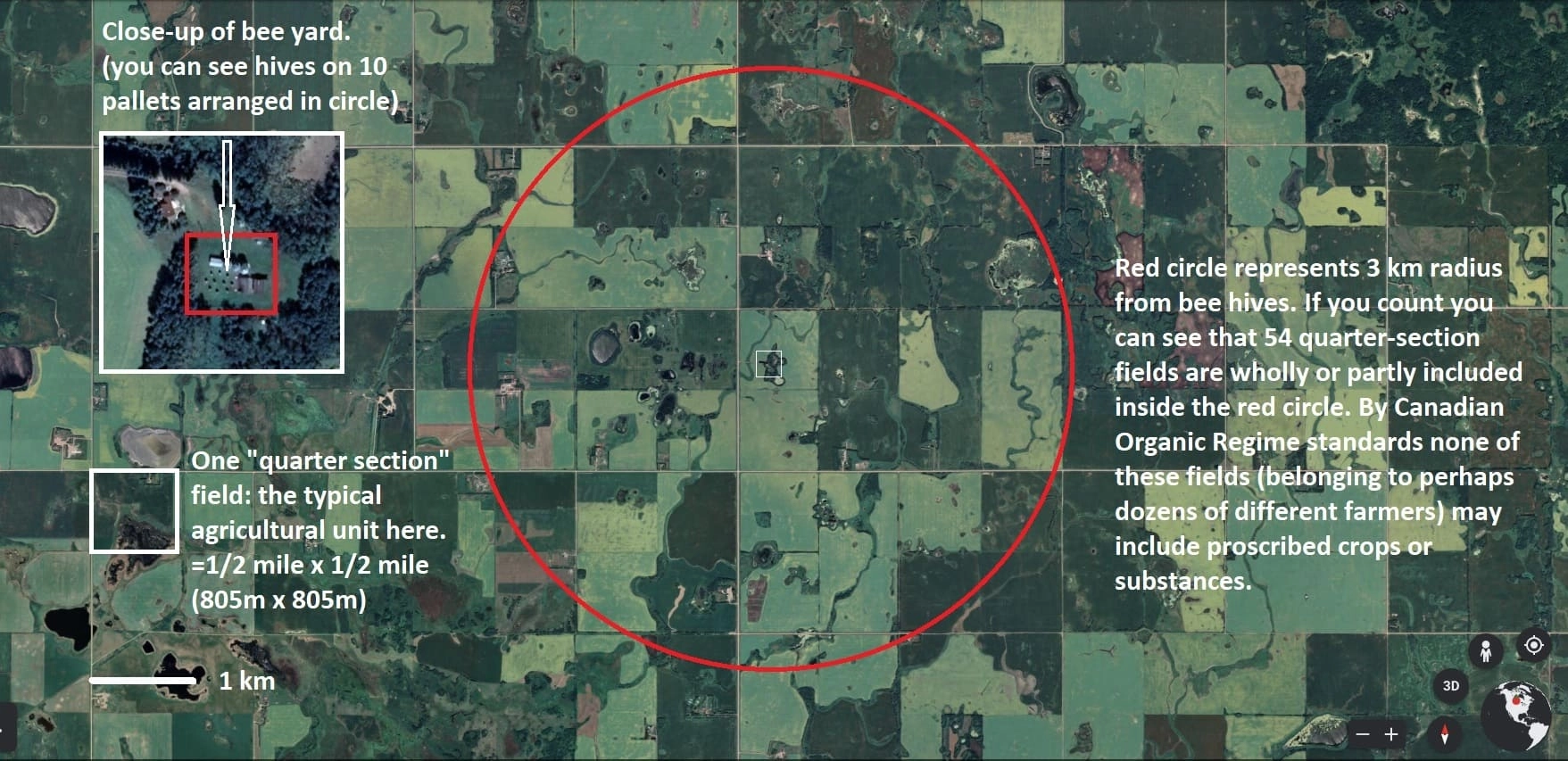

So far in both Canada and the USA, the principles of organic honey production are similar to other organic food production: to produce organic food, one must farm by agreed organic methods. However here is where it becomes quite complicated for honey: Bees forage nectar (and pollen, and water, and propolis, and honeydew) where they find it, up to as far as 5km (~3 miles) or more (!) from their beehive.2 Both COR (Canadian Organic Regime) and the NOP (USA’s National Organic Program) consider the honey’s nectar source and both define a 3-km (~1.8 mile)3 radius zone around the honeybee colonies (termed a “buffer zone” by COR and a “forage zone” by the NOP). Within the buffer/forage zone, land and crops must satisfy organic standards (as they apply to apiculture) in order for the bees in each apiary, and the honey that they produce, to be considered organic. Within this 2,827 ha (6986 acres) buffer/forage zone, GMO crops, chemical pesticides and herbicides and other soil and water toxins are prohibited. Beekeepers generally neither own nor control the land surrounding their apiaries. This land is managed by as many as a dozen or more independent farms, possibly also including parks, residential areas, and golf courses and bodies of water. The owner or manager of the land usually makes their management decisions independent of the beekeeper or apiary. The presence of an apiary, often in a sheltered location, up to 3km (1.8 miles) distant, may not even be known to some of the landowners.

Below is a real example of one of our own apiaries as seen in Google Earth. It is relatively easy to make out many of the square fields. In our part of Canada, a “field” is usually one “quarter section”: a half-mile by half-mile square of land (805m x 805m, 160 acres, or 64.75 ha). A farm here usually manages from 5 or 6 quarter sections for a modest farm, up to up to 10-20 for large farms.4 If you count the quarter sections are completely or partially within the 3km organic buffer zone, you should count 54 fields. Ownership of these 54 fields may be divided among several to dozens of independent farmers. If even one farmer plants a crop or employs an agricultural management technique not allowed by organic apiculture (beekeeping) regulations in just one field within that 54-field buffer zone, then all of the honey and all of the bees in that apiary become ineligible to receive organic certification, regardless of how rigorously the beekeeper practices organic beekeeping.

Where are these large swathes of land free from contamination and agricultural chemicals that could allow a beekeeper to have a chance at producing organic honey? There are some locations on the fringes of the main agricultural areas of Canada where less intensive agriculture is practiced. Beekeepers may be able to locate their apiaries in areas surrounded by organic farms, un-managed wilderness, grazing meadows and pastures, and/or hay fields. These locations are few and far between, generally difficult to access and may not produce sufficient honey crop yields for beekeeping to be sustainable.5

In the United States, where agriculture practices are generally more intensive, potential organic beekeeping locations are almost impossible to find. Even National Parks often employ proscribed chemicals to manage threats like certain moths. Chemical use in the management urban parks, golf courses or even private lawns or gardens often rules out organic apiaries within a 3 km/1.8-mile radius. Many American beekeepers rely on pollination fees to survive, especially with honey prices being below the cost of production for most American beekeepers in recent years due to honey dumping and the prevalence of fraudulent and adulterated honey on the market. A majority of American beehives are transported to California each spring for the almond pollination followed by pollination of other crops around the country. A honeybee colony would lose its organic status upon being moved to pollinate crops like almonds that do not follow NOP organic management practices. I suspect these reasons contribute to USDA’s reluctance to certify any domestic American honey as organic.

Because most commercial honey-producing beekeepers have many apiaries, it would be expected that most Canadian beekeepers that manage to receive organic certification for some of their apiaries, also have apiaries that are excluded by the rigorous requirements. Because equipment and bees for organic honey production and regular honey production must be kept entirely separate, the costs of managing a honey farm with some organic and some non-organic apiaries increase dramatically. There is also the issue that if a previously certified organic apiary becomes non-organic due to a change in crops or land management within the buffer/forage zone, not only is the current year’s harvest excluded, but also the next year (remember, honeybee colonies must be under organic management for at least a year prior to being considered organic). The result is that legitimate Canadian COR-certified organic honey is extremely difficult, expensive, and risky to produce.6

Why our farm isn’t certified organic (or even trying)

While we fully support organic agriculture and endeavour to adhere to the organic beekeeping practices as much as feasible (more on this in our FAQ), we don’t even consider seeking organic honey certification. Our honey farm has just over 4000 production colonies in just over 100 apiaries (numbers vary slightly from year to year, depending on winter losses and other factors). The added expense of managing organic apiaries completely separately from our non-certified apiaries is far from sustainable even with the higher price of organic honey. With the risk of any apiary losing organic certification due to agricultural practices completely out of our control, organic certification is a non-starter for us.

Get honey delivered fresh from our farm to your table.

Other countries

One can imagine that in other countries where agriculture is less intensive, there may be more opportunity to produce organic honey. We often imagine developing countries to be less reliant on large scale industrial agriculture, home to tracts of land that are more natural and organic, unspoilt by modern industry. This may be the case in some areas, but I’ve also been to low and middle-income countries where independent farmers apply doses of inexpensive chemicals that are more toxic than those currently approved for use in most developed countries.

Speaking recently with a former Provincial Apiarist, the topic of organic honey came up. We are both aware of honey producers in Canada that mysteriously produce “organic honey” while their apiaries are clearly not in locations that satisfy the COR regulations. As a former provincial apiarist, my friend has visited honey producing operations in other countries. He related the story of visiting a certified organic apiary in a developing country. Because this apiary was certified by its national organic certification board, the Canadian Organic Regime also acknowledged the organic honey designation and therefore it can be imported into Canada and sold as “organic honey”. He observed a man with a backpack sprayer spraying organophosphate pesticides (the empty containers were visible nearby) in a field adjacent to the bee yard. When he asked the beekeeper about that, the reply was “That is not spraying pesticides. There is no airplane: no crop dusting. That man is only ‘spot spraying’”. Trusting the USDA organic label on honey (and the COR organic label on imported honey) means trusting the organic certification process of the country where the honey was harvested and certified. Acceptance of foreign-certified organic honey by Canadian and American government agencies hurts their own domestic, more regulated, honey industries by disadvantaging domestic producers over foreign ones. It can serve to mislead consumers and undermine consumer confidence in government standards.

It is interesting to note that certified organic honey from some exporting countries fetches a lower price on the commodity markets than non-organic honey from Canada or the USA. It worth considering that the USDA-certified Organic honey from Brazil cost the honey brand owner less than regular honey produced in North America. One also wonders, given the price bump the word “organic” imparts, why big players in retail honey are willing to pay more for non-organic honey from North America. I’ve been told by a food distributor that our honey would not sell on store shelves because it is more expensive than organic honey: “no consumer will pay that much for honey that doesn’t have the word ‘organic’ on the jar. I don’t care about the industry reality. The consumer only sees the label.” However, the reality is that raw North American honey starts from a more expensive base commodity than at least some imported organic honey.

Some clarifications about “organic honey”

I should clarify some other common misconceptions. “Organic honey” is not the same thing as “raw honey”. Raw honey is unprocessed honey in the state that it would be exist in the beehive. Organic honey can be processed, ultrafiltered, heated and pasteurized just like any honey. The cheapest organic honeys on supermarket shelves are often honeys processed in this way. This processing destroys and removes some of the honey’s health benefits and unique and complex flavours of the honey, while also making fraud and adulteration more difficult to detect. Normally raw, non-organic honey is a better health choice than processed organic honey. Raw honey is closer to its natural state, has all of its healthy flavinoids, enzymes, vitamins and pollen intact, and will have a more complex, natural flavour profile. If I were to choose between a processed organic honey and a real, raw honey, I would choose the raw honey every time. Of course, you can have unprocessed certified organic honey that is also raw. This hard-to-find honey is seen as the gold standard in terms of being safe, healthy, natural, environmentally friendly, and full of flavor.

In principle, organic certification of honey ensures that the honey is free of antibiotics, agricultural chemicals and toxic environmental contaminants since, with the implementation of the buffer/forage zone, organic honeybees should not even encounter these hazards. This does not mean that honey lacking organic certification contains more harmful substances than organic honey: It simply has not been certified to specific organic apiculture standards. Much (likely the vast majority of) Canadian honey lacking organic certification is completely free from pesticides, antibiotics, and other known health hazards. Every honey producer in Canada is expected to adhere to regulations governing the use of veterinary pharmaceuticals and honeybee feeding practices. One main purpose of these regulations is to prevent honey contamination by potentially harmful substances. It is common practice within the industry for honey traders, honey packagers and brands to test any honey (organic or not) for harmful substances before that honey goes into retail packaging. No brand wants to be faced with the scandal of a recall due to potentially harmful contamination.

Final Thoughts

As beekeepers, we applaud the movement towards more natural, organic and holistic agriculture. Industrial monocrop agriculture is conducive neither to raising healthy honeybees, nor to promoting healthy populations of natural pollinators. Honeybees and beekeepers would like to see minimal amounts of agricultural chemicals released into the environment, but ultimately management of the land surrounding apiaries is out of the beekeeper’s control. In Canada, organic certification of honey involves not only adherence to organic beekeeping practices but also having a 3 km radius around each apiary in which the independent farmers and land managers also follow these policies. The same principles apply in the USA, but it is currently not even possible for American honey to receive USDA organic certification, which is granted only to imported honeys.

Correction

2023.07.06 USDA doesn’t certify honey directly as organic: It relies on certifying agencies to do that. Despite the USDA not having formally adopted the NOP organic honey guidelines, it may be possible in some extremely rare circumstances that a certifying agency would certify domestic American honey as organic (here’s the full update)

Footnotes

- Miticides are treatments to kill or control mites, especially the varroa mite that has been decimating North American beehives. The varroa mite is currently probably the largest threat to bee colony (and beekeeper) survival. Many feel that without effective options to control varroa mites, organic beekeeping is doomed. Miticides that occur in nature – formic acid, thymol and carbon dioxide can be used in organic honeybee colonies.

- Bees don’t read the organic rules, and they are extremely difficult to fence in or confine to certain areas. “Free Range Honey” could be the next marketing gimmick. It would certainly be true more often than “wildflower honey” moniker (see 5 below).

- I just said bees can fly up to 5km to forage (I have seen a distance of up to 12 km mentioned). So why do both the NOP and COR use only a 3km forage/buffer zone? Studies have shown that due to the energy economics and mathematics of foraging, the vast majority of nectar is foraged from within a 3km radius.

- We feel fortunate that grain and livestock farms in our area are still largely family-owned farms rather than corporate enterprises.

- In order for a beekeeper to be able to harvest honey, the bees need to be able to produce an excess of honey. For commercial beekeeping this requires a relatively high density of blossom during at least part of the year. In Canada, and probably also in the USA, this generally requires at least some agricultural crop contribution. I think that harvesting honey that is mostly foraged from wildflowers in Canada is so rare as to be almost impossible commercially. Wildflower blossoms in true wilderness in Canada simply aren’t dense enough to allow a viable commercial harvest. I am always skeptical of honey labelled “wildflower honey”, especially if it’s from North America. This strikes me as a blatant marketing gimmick. While our honey certainly has a component of wildflower in it, we won’t go so far as claiming it is “wildflower honey” as it also certainly has some agricultural blossom honey in it.

- Where there is profit to be made, there will be scammers. Some Canadian honey producers (a very small minority) whose farms are in agricultural areas in which organic farming is not common produce a mysterious amount of “organic honey”.

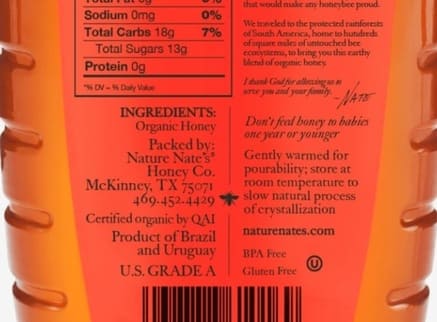

- While this inexpensive honey looks healthy and natural from the front label, several things can be observed on the back. At best it is a blend of honeys from Brazil and Uruguay, certified as organic in those countries. While it claims to be “raw” the back label describes it as “gently warmed”: This company has been named in a lawsuit for mislabelling the honey is raw when it had been shown by hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) testing to be heated, and for selling honey that had been adulterated with sugar syrup. A final note is that the nutrition label claims 18g carbohydrates per 20g serving (this is normal), sugars are listed as only 13g/serving (this is very abnormal). The carbohydrates in natural honey are at least 99% sugars – glucose and fructose.

Jeremy Wendell

Share this story

3 comments

[…] honey labelled as organic in the United States and Canada, may be at higher risk of contamination. Certifying honey as organic becomes quite complicated because honeybees forage for nectar unconstrained over large areas. Much organic honey is imported […]

[…] honey labelled as organic in the United States and Canada, may be at higher risk of contamination. Certifying honey as organic becomes quite complicated because honeybees forage for nectar unconstrained over large areas. Much organic honey is imported […]

[…] honey labelled as organic in the United States and Canada, may be at higher risk of contamination. Certifying honey as organic becomes quite complicated because honeybees forage for nectar unconstrained over large areas. Much organic honey is imported […]