Beekeeping at Wendell Honey

In the early years, John Wendell would purchase package bees from the United States in the spring. These colonies would bring in the honey over the summer and, come fall, they would be killed as it was not thought feasible to attempt to keep the bees alive through the harsh prairie winters. Increasing concerns about importing diseases diseases not yet present in Canada led to increased restrictions on importing bees in 1986. Packaged bees could still be imported from certain countries, like Australia or New Zealand but at much greater expense.

Changes in beekeeping practices with closure of the Canadian border to American package bees and increasing bee diseases encouraged Tim to start keeping the bees over winter. Surviving Canadian prairie winters outdoors requires healthy, well-adapted bees. Tim started raising his own queens in the late 1980s in an attempt to increase disease resistance and winter colony survival rates by breeding from queen bees that had shown to be disease-free and produce a lot of honey. These queens had proven genetic suitability to our local environment and climate conditions. Queens were raised in nucleus hives that would replace winter losses in the following spring and summer. (The Manitoba Cooperator interviewed Tim for an article on raising bees in Canada here.)

Wendell Honey’s queen rearing program is a key component to our success as a honey producer. Although we do share some Wendell queens with our Organic Honey partners or other beekeeping friends, Wendell Honey is not in the business of selling queens or package bees: we raise our queens for use on our farm, to make up for winter colony and/or queen losses. Although our average winter colony loss is well below the North American, Canadian and provincial averages, it is inevitable that some colonies die off each year, usually during the winter. The queens we raise hatch out into a mini-hive called a hive nucleus, or “nuc” for short. These nucs are started in late spring or early summer and by the following spring are mature hives with young energetic queens ready to replace any winter losses.

Breeder queens are selected for several important traits: suitability to the local climate, productivity, non-aggressive nature, hygienic behavior and natural disease resistance. Successively breeding many generations of queen bees combined with selective cross-breeding with other strains has gradually resulted in highly-productive, disease-resilient bees that are well-adjusted to our local environment and gentle enough that we often work with minimal protective clothing. Tim’s research connections come in handy when sourcing outside genetic stock with desirable characteristics helpful in maintaining hybrid vigor. In addition to Tim’s 4 decades’ experience breeding queens, Zulema, Dan and Eli, Randy and Edward have combined experience of over 10 decades raising queen bees in South America, USA, The Philipines, Mexico, Europe and Canada. Watch the Queen Team in action here.

Careful breeding and constant attention to the well-being of every one of our thousands of hives has meant that even while many beekeeping operations suffered catastrophic losses due to colony collapse disorder, our thriving hives survived the Canadian prairie winters outdoors and each summer continued to produce honey crops easily exceeding the Canadian and Saskatchewan average yields. (The interested can check out this PBS documentary on colony collapse disorder here)

Update: We were not spared the disastrous effects of the 2021-22 winter.

We care deeply about the health and well-being of our bees. To start with, apiary (bee yard) locations are carefully chosen to provide the bees with the optimal environment. Consideration is given to shelter from the winter winds, sun exposure, proximity to a clean water source and availability of pollen sources early in the spring when it is most critical. Any apiary in which the colonies fail to thrive is moved to a new location. Our team of beekeepers begins checking the condition of every single one of our 4000+ honey-producing colonies as soon as the weather is warm enough that opening the beehive will not cause harm. Each colony is examined for queen status, bee population, food supply (honey and pollen), disease and hygiene. Until harvest begins in July the team continuously checks and supports the colonies: cleaning hives of debris accumulated over winter, treating any survival-threatening diseases, supplying honey or pollen to colonies with inadequate supplies and providing queens to queen-less colonies. Each colony is examined at least 3 times prior to harvest. From harvest until winter any hive which shows signs of failing is checked.

We inhabit the same environment that our honeybees do. As we feel a deep connection to nature, we’ve implemented various sustainable beekeeping practices over the years to protect the local environment we share with our bees.

With short prairie summer of long sunny days and abundant blossoms, our harvest season is intense. A single healthy beehive can produce up to 15 kg of honey on a good summer day. We harvest this honey from July until the beginning of September. We employ minimally invasive harvest techniques: the queen/brood chamber is not disturbed. We do not use any chemical repellents to force the bees from the honey supers, but rather allow the bees to fly out on their own and then used forced air to remove the few remaining bees from the honey supers.

The field teams bring full supers of honey in from the field to the “honey house” where the extracting and bottling facilities are housed. The next day the extracting crew scrapes the wax cappings off each honeycomb and then the honeycombs are loaded into a centrifuge that spins the honey out of the combs. Depending on the qualities of the honey it is then pumped either into the bulk canning tanks and into large drums for bulk sale to honey packing companies, or, if it meets our Wendell Estate standards, the honey goes directly into the Wendell Estate storage tanks. The liquid honey passes through a couple 80 mesh screens to have larger pieces of wax removed and then is bottled fresh on the farm. Our honey extraction and bottling facilities use only Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA)-approved, food-grade stainless steel equipment.

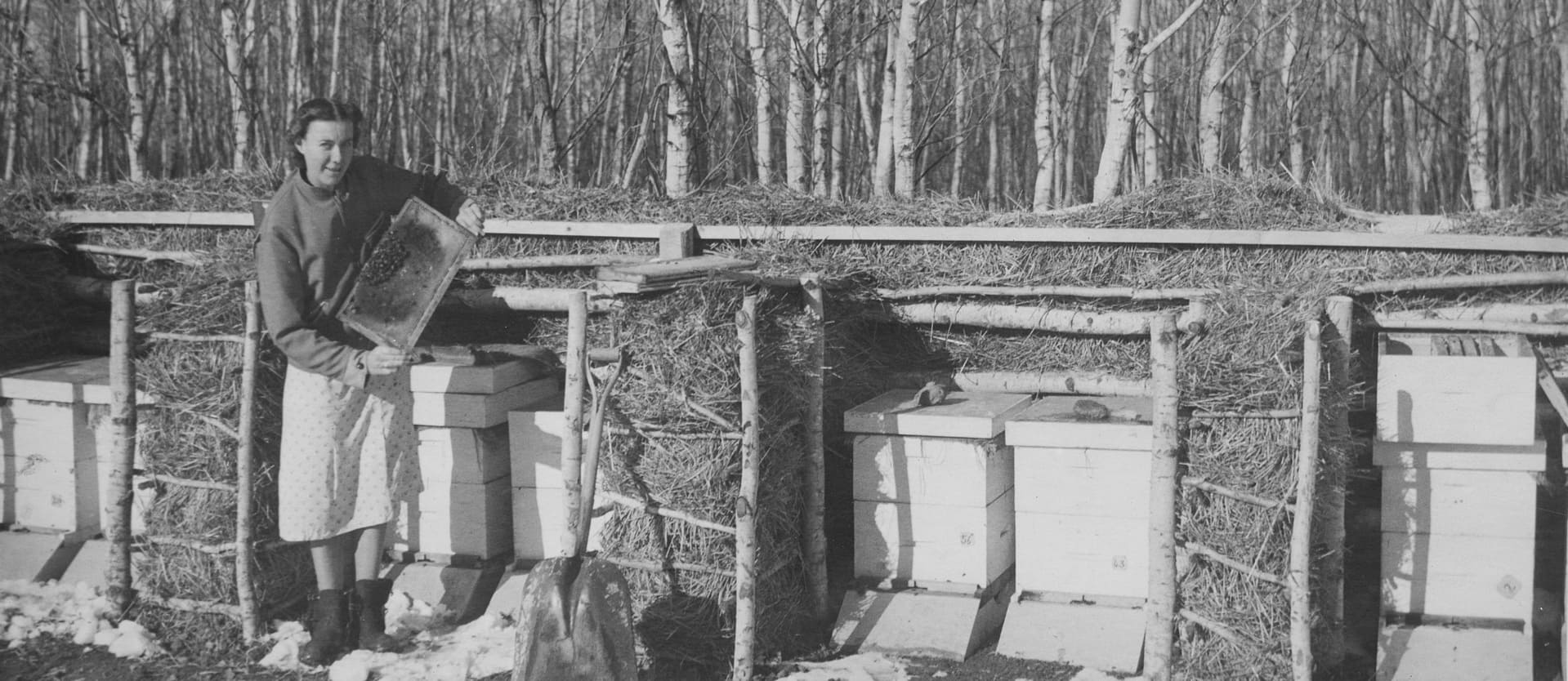

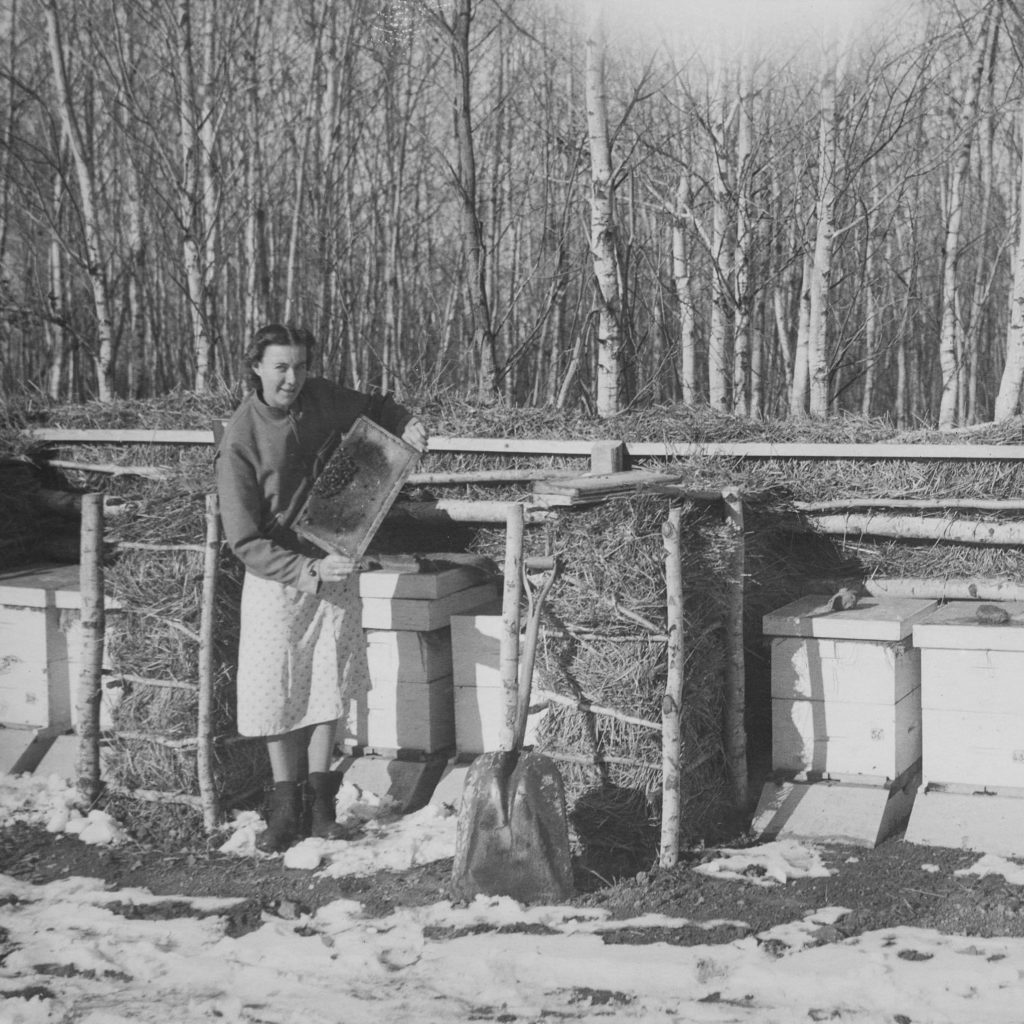

Harvest winds up at the beginning of September. The next couple months are spent getting the hives ready for winter: making sure they are healthy and have adequate food stores. Finally, the hives are pushed together in groups of four for warmth, wrapped with insulation and left to hunker down and keep warm by eating and metabolizing honey until the next spring.