Pasteurized vs Unpasteurized Honey: What’s the Difference?

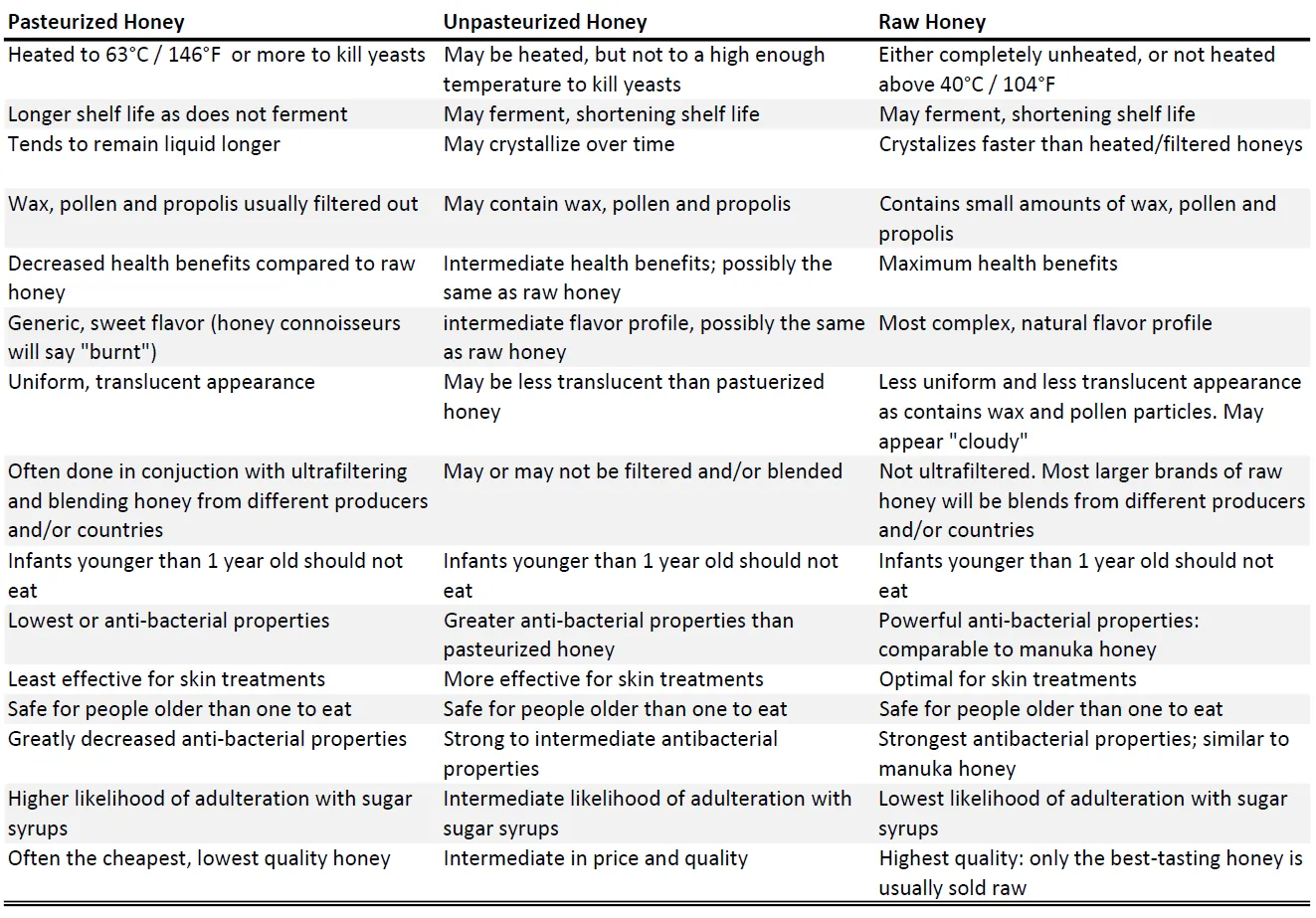

Pasteurized versus unpasteurized honey is an important distinction when it comes to choosing honey. I’m going to try to clarify the differences between these two honey categories in this post, by defining each category and explaining the differences. I’ll also go a bit into an important subset of unpasteurized honey, raw honey.

What is Pasteurized Honey?

Pasteurized honey is honey that been heated to kil the naturally occurring yeasts that are often present in raw honey. To pasteurize raw honey, the honey is heated to a high enough temperature, for a long enough time to kill the yeasts. Different pasteurization methods use different combinations of time and temperature. I’ve seen temperatures from 63°C / 146°F up to 75°C / 167°F. Sometimes pressure is used to alter the time and/or temperature needed to kill the yeast. The main point is that the heat kills the yeasts.

Why Pasteurize Honey?

Heating honey to pasteurize it is done for several reasons:

- Kill the yeasts that are often present in raw honey, prolonging shelf life by preventing fermentation

- Lower the viscosity of the honey, making it faster and more economical to filter the honey as and package the honey into retail jars

- Dissolve the natural sugar crystals in the honey (about 80% of raw honey is the natural sugars glucose and fructose, in approximately equal proportions depending on the floral source of the honey). This slows the crystallization process of the honey, allowing it to remain liquid longer and contributes to processed honey’s uniform translucent appearance.

- Reduce the water content of honey, which also reduces fermentation and can raise the value of the honey that’s harvested prematurely (before the bees can dry the water).

What Pasteurizing Doesn’t Do to Honey

Since Louis Pasteur first accidentally discovered the food safety benefits of pasteurizing milk, the term “Pasteurized” has come to denote increased food safety. With honey, pasteurization does not increase food safety at all (and in some ways pasteurizing honey may decrease food safety ). Pasteurization of dairy products and other foods is usually done to increase safety by killing harmful bacteria, thus preventing serious bacterial infections. Bacteria cannot live in raw honey (a big reason why raw honey is such a naturally safe food), so pasteurization doesn’t make raw honey any safer to eat. I can’t emphasize enough the fact that unpasteurized honey is as safe (or safer) to eat as pasteurized honey1.

Any honey can contain inactive spores of Clostridium botulinum, which can cause infant botulism if eaten by infants less than 9 months old2. The temperature used to pasteurize honey is not high enough to affect the C. botulinum spores, so infants younger than one year of age should not eat any honey, pasteurized or not. For people older than one year of age, any C. botulinum spores accidentally consumed pass harmless through the digestive system. C. botulinum spores cannot cause food-borne botulism3.

Where does raw honey fit in?

Raw honey is a subset of unpasteurized honey. Though there’s no official, legal definition of raw honey, the term refers to honey as it exists in its natural state: honey that you would find in a beehive. The commonly accepted maximum temperature that raw honey can be exposed to and still be considered raw is 40°C or 104°F, which roughly corresponds to the maximum temperature honey would be exposed to inside a beehive on a very hot day. Raw honey is also assumed to be pure and unfiltered, meaning that it will contain small bits of wax and often bee propolis as well as bee pollen.

All raw honey is unpasteurized, but not all unpasteurized honey is raw. Raw honey may be exposed to heat at various stages aside from pasteurization. The other main reason to heat honey is for packaging it. Most supermarket brands of honey (raw honey included) are large brands that source their honey from multiple producers, often from different countries. They get honey in bulk drums at ambient temperature and the honey is often partially crystallized. The honey generally needs to be heated to melt any crystals and decrease the viscosity in order to package it into the retail jar. This can be done at temperatures below the 40°C / 104°F limit of raw honey, but the higher the temperature, the less viscous the honey and the lower the packaging costs. Honey that is unpasteurized, but not raw, would likely be heated above 40°C, but not pasteurized, at this stage. However, I have good reasons to suspect that some honey marketed as “raw honey” is actually heated above 40°C to package it and still labelled “raw”. Here’s a more detailed look at fresh raw honey.

What are the key differences between pasteurized, unpasteurized and raw honey?

Though unpasteurized honey hasn’t been heated to a high enough temperature to kill the yeast, it still may have been heated to a lesser temperature in order to facilitate filtering the honey to remove particles (wax and bee pollen) or package the honey. If unpasteurized honey has been ultrafiltered, much or all of the wax, propolis and bee pollen will have been removed. Some things worth noting:

- Honey is usually still considered raw if it has been strained to remove larger pieces of wax. The filtering of most processed honey above (often referred to as “utrafiltering”) uses a very fine mesh that removes all small particles, including pollen.

- The natural yeasts killed by pasteurization are entirely harmless if eaten. However, when honey absorbs moisture from the environment (usually the air – honey readily soaks up water), yeasts can cause unpasteurized and raw honey to ferment. Pasteurization is done to prevent this and extend shelf life. Eating fermented honey also poses no health risk whatsoever, but many find the sour, yeast-y taste unpleasant.

- Likewise, eating wax is completely harmless. Wax simply passes right through our digestive tract and exits unaltered, doing neither harm nor good.

- Bee pollen contains vitamins and minerals, so it is considered healthy to eat. Bee pollen is commonly sold as a natriceutical. I will mention that the amount of bee pollen you would consume while eating raw honey is tiny, so it won’t have any significant effect on health4.

- Bee propolis, like bee pollen, is thought to be beneficial to health. Like bee pollen, the amounts of bee propolis that you would get from eating raw honey would be tiny.

Health Benefits and Pasteurization

For many, an important thing to consider when deciding which kind of honey to buy is the health benefits. Raw honey’s numerous health advantages are becoming increasingly well-known, and researchers are continuously discovering more potential benefits of raw honey (for example, eating raw honey regularly may decrease the risk of some cancers). Many people don’t realize that if you’re eating the honey, any raw honey has similar health benefits to those widely advertised by manuka honey: manuka marketers simply want consumers to believe these are special properties of manuka honey. They are not5.

That raw honey is healthy is backed by dozens, if not hundreds of scientific studies. However, the reasons why raw honey is so healthy aren’t fully clear. Many health benefits of raw are thought to derive from the different bee enzymes, organic polyphenols and flavonoids that come from either the source flower nectar or the bees themselves as they process and mature the honey. Like most organic compounds, these compounds tend to be destroyed when heated. The more the honey has been heated, the fewer of these health-giving (and flavor-giving) compounds remain intact in the honey. By now, it is indisputable that raw honey offers more health benefits than pasteurized honey. This almost certainly explains raw honey’s increasing popularity. Heating also alters the flavor, so raw honey will have a more complex natural flavor than pasteurized honey.

Another heat-sensitive component in any raw honey is the enzyme glucose oxidase. This is the enzyme responsible for much of raw honey’s remarkable anti-bacterial properties and a main reason raw honey is so safe to eat almost regardless of how it has been stored. Heating raw honey rapidly denatures glucose oxidase, decreasing the honey’s natural anti-bacterial properties. Any raw honey has natural anti-bacterial properties comparable to manuka honey, but unlike manuka honey, most other honeys’ anti-bacterial properties are greatly decreased by heating or pasteurization. So if you are using honey as a skin treatment, you should choose either (any) raw honey or a honey like tualang or manuka that have special, heat-stable anti-bacterial compounds.

Notes

- I often see it mentioned as a “fact” online that “raw honey can harbor harmful bacteria”, or some variation on this. This is simply incorrect. Bacteria, even the “superbugs” that are resistant to many antibiotics, cannot survive in pure, raw honey. There are many credible, medical sources to support this, including the world-renowned Mayo Clinic. This is true of any natural raw honey, not only manuka honey (as manuka honey marketers would have you believe).

- Usually 1 year is quoted as the age in which children can safely eat honey. This adds a safety margin to this rare, but serious health hazard of honey when eaten by young infants.

- Infant botulism is caused by C. botulism spores attaching to the wall of the immature intestine and then germinating and growing. Growing C. botulism bacteria create botulinum toxin as they metabolize. This is a neurotoxin that causes the symptoms of both infant botulism and food borne botulism. Food born botulism is a related disease in which food contaminated with large amounts of botulinum toxin (any bacteria also ingested with the spoiled food are virtually irrelevant here – it is the toxin that causes the acute illness). The very high dose of ingested botulinum toxin with food-borne botulism can cause serious acute illness or even death. C. botulism spores present in honey are inactive and cannot produce botulinum toxin so you can’t get food-borne botulism from honey.

- Removing bee pollen from natural honey has a downside apart from the (very small) nutritional health benefits in the minuscule amounts of pollen in natural raw honey: The pollen in honey helps determine which flowers and which geographic area or country the honey came from, as well as whether the honey is authentic, or whether it’s been adulterated by cheaper sugar syrups. This means it’s more difficult to determine the origin (geographic and floral) of processed honey, and whether has been adulterated either with sugar syrups or illegally imported, possibly contaminated or adulterated honey.

- What is special about manuka honey is it’s rather uniquely suitable among honeys for making heat-sterilized, medical wound dressings. This is what the MGO and UMF represent – potency of antibacterial properties after heat-sterilization, not overall health benefits when the honey is eaten instead of being used as a heat-sterilized wound dressing.

Share this story